by James Zug

Day Two

2-6, 2-6, 3-6, 6-5

Day Two was quite different than Day One at Prested Hall.

There were new faces onsite. Owner Mike Carter, who dreamed up Prested twenty-eight years ago, returned from Spain. Former world champion Penny Lumley appeared. A second American-based professional, Conor Medlow (Chicago), joined Penny’s son John (Philadelphia) in the galleries. The weather was suddenly autumnal, chilly and damp, with rain threatening and then finally in the third set some spitting turned into a steady, light patter. And everyone was attuned to historical resonances after the fourth annual International Conference on the History of Tennis—four-string guitar and fourteenth-century singing, awards and discussions all concluded.

History was perhaps not on the side of the champion. Only twice in his previous fourteen Challenges had Rob Fahey split the first day’s four sets. Both times it was against Camden Riviere, in 2008 in Fontainebleau and 2014 in Melbourne, and both times he had managed to turn it around on the second day, winning three of the four sets to take commanding, and it turned out impregnable leads.

But now it was different. Fahey, grey-haired and avuncular, has become the professional ranks’ elder statesman. He’ll turn fifty-five next April. He’s playing someone who is more than six points better off handicap and who wasn’t even alive when an eighteen-year-old Fahey first walked off Davey Street and onto the famous tennis court in Hobart. The last we had seen him on the conclusion of Day One, he was in flip-flops having a beer by the bar, clearly pleased he copped two sets. Could Fahey summon the old magic one more time on Day Two? Would the balls—a final set (of eighty not the usual seventy) made by master ball maker Steve Ronaldson two and a half years ago—soften enough to provide any bite for him and his classic railroad on the slick, sleek, smooth Prested penthouse or help him retrieve a tiny bit better?

To learn the answers, another sold-out crowd of two hundred spectators filled out Prested Hall’s glass court, and a nearly equal number around the world joined on the live stream, captivated by the dozen camera angles and instant replays adroitly operated by Ryan Carey and the commentary offered by Robert Shenkman and Lewis Williams, Leamington’s dynamic duo.

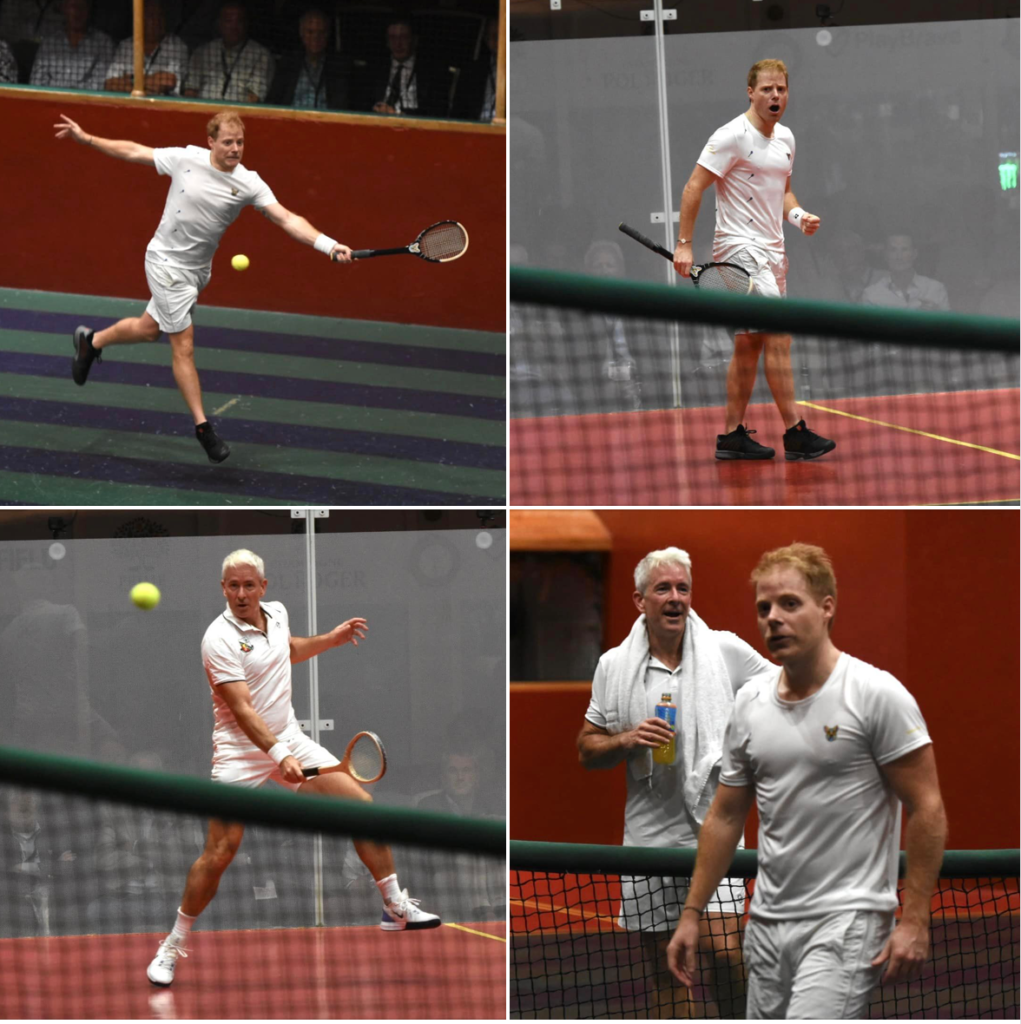

Riviere, sporting black sneakers this time, continued to serve to start the fifth set, having been serving when the fourth set had concluded forty-nine hours earlier. Fahey greeted him with a main-wall force the first time he touched the ball. Hello. On the next point, Fahey cannoned a drive to the nick, chase worse than three. Riviere managed to beat the chase but Fahey, with two dedans forces and a rocket to the grille, clearly needed not a moment to settle in.

The fourth game was pivotal. It lasted almost fifteen minutes. Fahey squandered six game balls, Riviere two, before Riviere hammered it home. He quickly threw away the next game but then took the next three with relative ease. A pattern emerged. Respect the bobble was the watchword. Riviere doubled down on the serve, hitting it every time and with more effectiveness than on Day One. Very often Fahey had to boast a return off the side wall or chop at it. It produced ten outright errors from Fahey and many more balls that Riviere could dig out with his trademark jackrabbity speed. Fahey was unable to get the ball in the back of the dedans net (he had just two more forces after the first game and only one grille). Riviere was confident, at ease. He varied the pace: some blistered line drives, some feathered, shaped arrows to the corners. And his retrieving was incredible: always balanced, always moving to the ball like liquid mercury.

Riviere again lost the first game of the sixth set, again went up 3-1, again lost the fifth game and then again went on cruise control. Fahey tried to slow it down: he faulted a dozen first serves and allowed marker Andrew Lyons the opportunity to clear any ball on his side of the court. He tried to force but Riviere defended brilliantly—it was a bad sign for Fahey that Riviere had twice as many forces in the sixth set as he did. Instead, unforced errors began to plague Fahey. Too many balls crunching onto the penthouse, too many flubs into the net. He even tried a behind-the-back stroke and only caught air.

The seventh set started the same, Riviere hopping to a 4-1 lead. Then it unexpectedly tightened and Fahey reeled it back to 4-3. Riviere, up the task, showed world-class skill. He caressed a ball into the backhand corner to beat a chase of worse than a yard and soon cracked two balls into the grille. In short order, he had the third set of the day.

It accelerated. Riviere flew to a 4-0 lead. A bagel day loomed. Fahey looked tired. It was over. And really over. With a lead of six sets to two, Riviere would be, if history was a guide, certain of victory. In two centuries of Challenges, no one had ever won five sets on a third, final day. Punch Fairs snagged three in 1904 in Brighton but fell short to Peter Latham; Lachie Deuchar took three in 1993 in New York but fell short to Wayne Davies; and of course Tim Chisholm electrified the world when he grabbed the first four sets on the final day at Hampton Court in 2002 but could just not finish off Fahey in the thirteenth set.

The old champion had one more push. 4-1. 4-2, 4-3. Could he really come back? He didn’t hit a single target in the first four games; in the last seven he smacked ten dedans, two winning galleries and one grille. Simply spectacular. The crowd, hitherto subdued, roared with approval. Riviere responded and built back to a 5-3 lead, but tension was thick in the Essex air. Riviere had four sets points. Four times, Fahey survived. He began to gesticulate to the crowd, fist-pumping, waving a No.1 finger.

5-5. During a wild point, someone in the clerestory shouted loudly when it appeared a Riviere ball had gone out of court. Both players hesitated; Riviere soon finished off the point; but a let was called and the point replayed. Fahey dashed to 40-0. Riviere saved two nail-biting set points but couldn’t manage a third.

After exactly two and a half hours of play on Day Two, Riviere had a 5-3 lead, but Fahey was still decidedly in the match. His feet ached. He had changed sneakers after the seventh set and as soon as he finished, he was back in his flip-flops. But there was hope.

Fahey and Riviere talked at length at the net and then a half hour later at the bar. Beyond the many, many times they’ve played against each other in regular tournaments, this was their fifth Challenge together. No two players in history had ever undergone this most intimate of trials that many times. They had a unique bond. This eighth set in 2022 might have been the most dramatic, most intense of the fifty-one Challenge sets they had so beautifully and brilliantly shared.

PHOTOS BY TIM EDWARDS