by James Zug

Day One

Camden Riviere won the first four sets 6-4, 6-2, 6-3, 6-4

It was a remarkable scene at Westwood Country Club, just outside Washington City, in the suburb of Vienna. There are sixteen states in the U.S. that have a town named Vienna, but it was the Virginia one that now could boast the record for hosting the Challenge Round of the World Championship. The shortest time between a court’s original opening and hosting a Challenge: Philadelphia was just six and a half years old when it hosted in 1914 and the marble court in Dublin was just five years old when it hosted in 1895. But now Westwood, officially just ten months old since its grand opening in November 2022, was welcoming the world to the greatest tournament in the game.

It was also the end of an era. Today was the first time in forty-two years, since Chris Ronaldson and Howard Angus faced each other at Queen’s Club in 1981, that an Australian did not play in the Challenge. A stunning statistic, especially considering that before 1981 an Australian had never played in a Challenge. There were still a half dozen Aussies in the galleries, including Rob Fahey, the former world champion, and another dozen promising to descend on Westwood for the Second Day, but not having one out on court gave the atmosphere in the galleries a decidedly different and perhaps slightly more subdued flavor.

The two players: the champion, Camden Scott Riviere. The thirty-six-year-old, ginger-haired southpaw (on RealTennisOnline he was dubbed the Ginja Ninja) hadn’t lost a regular best-of-five tournament match since January 2013 when Steve Virgona (on hand at Westwood as a training partner for the challenger) topped him at the Australian Open in four sets. Since the decade since, Riviere had captured thirty-eight singles tournaments in a row, only once going even to five sets in a final. (Let’s not dilate on his doubles prowess.) The only blots in his singles copybook over that time were his losses in Challenges in 2014 and 2018. His handicap was a plus 17.5.

John Colin Lumley, the challenger. Lumley was a right-hander with a plus 10 handicap (obviously taken with a grain of salt, as it is hard to get good handicap movement at that level). He was nicknamed The Hare, both because of his rabbity movement around the tennis court and his ability to keep every strand of his jet-black hair perfectly coiffured through a match. Lumley turned thirty-one last month. He was mentored by two world champions—his mother, Penny, who captured the women’s title six times; and Chris Ronaldson, the three-time world champion, who was the head pro at Radley where Lumley apprenticed for the first three years of his professional career. That was a serious pedigree.

Nonetheless, the odds greatly favored Riviere, not only because of his win streak. Only five times since 1885, when the World Championship began in earnest with regular Challenges, has a challenger managed to beat the reigning champion in their first attempt: Tom Pettitt in 1885, Peter Latham in 1895, Jay Gould in 1914, Norty Knox in 1959 and Rob Fahey in 1994.

There was a reason for that. There was the psychological pressure of sustained play, point after point, hour after hour, the relentless pressure with nary a break. And two days later, the players had to do it again. It usually took time to learn how to adapt.

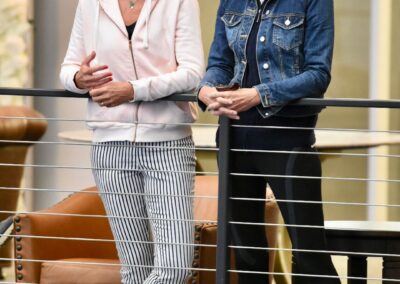

The afternoon was autumnal—in the low seventies and passing showers—began with a somber note. Alistair Curley, the master of ceremonies, greeted the overflow crowd and welcomed everyone. He then said that Temple Grassi, a driving force behind tennis in America and the creation of the Westwood court, had died exactly two years ago today. “It was his dream to have Washington host a world championship,” Curley said, “and today we remember Temple, our wonderful ambassador to the game, as we reach that goal.”

After the beautiful renditions of the British and American national anthems by baritone Ben Edquist, the marker, Ivan Ronaldson and the marker’s assistant in the grille, Matty Ronaldson, appeared. Ivan flipped a Maya Angelou quarter, Riviere won the toss and elected to serve. Riviere was in all white (shoes, wristband), except accents of black—his Wayward racquet, the Wayward logo on his shirt, his socks, his compression shorts. Lumley was more colorful, with gray sneakers with orange accents.

The first set. Lumley started off strong, laying down two chases before a point was determined and winning the first game. It was neck and neck for a while, as both players got into rhythm. Both hit primarily railroads for first serves (Westwood’s penthouse was very smooth and other serves didn’t grip and take cut) and bobbles for second serves. Riviere’s were just about ten percent better on both accounts, pinning Lumley down and forcing him to boast his return, while Riviere was able to attack and smack returns off Lumley railroads for chases or even forces. Riviere went up 5-2 but then Lumley clawed two games back, including clinching the ninth game after a spectacular rally. But Riviere clinched it. A pattern emerged, as Riviere was able to end points more often than Lumley: Riviere had four forces, two winning galleries and one grille, while Lumley totted up just one force and one grille. It was a forty-minute set.

The second set was faster and more one-sided. Riviere upped his grille total to six, including two in the first game; and one force; Lumley had one winning gallery and one grille. Riviere flew to a 4-0 lead and after a bit of a pull-back by Lumley, where he saved a couple of set points, took it 6-2.

An unexpected eight-minute break after the second set—Ivan mopped the floor and the players could change shirts—gave Lumley a chance to regroup. He won the first game of the third set and after Riviere went up 3-1 Lumely was able to peg it back to 3-3. For the third set in a row, the champion, however, won the decisive seventh game of a set. It was a long one, Riviere squandering game points and saving them as well. (Lumley had well more than a half dozen game balls throughout the match that he was unable to convert, including three in the third set when he was up 40-0 at 5-3.) Although Riviere snagged the last three games, he looked discomforted by his left forearm cramping and some evident red-faced fatigue. At the change-overs, he ate bananas and drank electrolytes but the last two sets still saw him shaking and stretching his hand in between points. Still, Riviere was able to compile an admirable amount of opening (four forces and three grilles), while Lumley had just one force and one grille.

The final set of the day was tight with tension. Lumley went up 2-0, but he was unable to stretch it out and see any real daylight between him and Riviere. The momentum shifted, perhaps when Lumley broke a string in his racquet and Riviere squeezed off four straight games. Lumley grabbed the seventh game. Riviere got it to 5-3. Lumley snatched one back; and then Riviere finished it off. Like the other three sets, a key difference was Riviere’s ability to put the ball into a point-ending gallery while Lumley struggled to do likewise: Riviere had eight forces and five grilles, including a dramatic one to take the set; Lumley had just four grilles and no forces or winning galleries. He had bad luck. At one point, playing off a chase of one and two, Riviere’s force missed under the dedans and came rocketing out to hit Lumley as he tried to dodge out of the way. Lumley saved two set points but not a third.

After two hours and fifty minutes, the first day ended with the champion up 4-0.

Photos by Tim Edwards

—

By James Zug

Day Two

Lumley won 6-4, 3-6, 6-5, 6-5. The match is now 5-3 in favor of Riviere.

It was an extraordinary Day Two at Westwood, one of the great classic Day Twos in the history of the World Championship, evocative above all of the Day Two at Queens in 2018.

Today the galleries were slightly less dotted by patron gift bags, which were overflowing with local chocolate, the tournament program and two frameable items—the official poster and a Mikko postcard. During the pre-match cocktails upstairs, the canaille enjoyed the two players’ favorite drinks: the Lumley (vodka, pineapple juice, lime juice, sparkling water and a lime) and the Riviere (Sipsmith gin, tonic water and a lime).

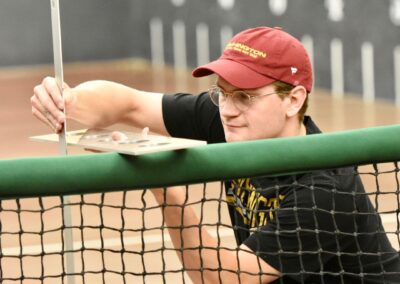

From another off-court oubliette, Ryan Carey again streamed the event, his second world championship. Twice in Day Two a player’s force to the dedan dislodged one of Carey’s cameras hanging there like bristling guns in a turret. The championship balls—eighty for the match and sixty for practice—had been made for this Challenge by Darren Long at Manchester, after a thirty-year tradition of Steve Ronaldson making world championship balls. Tim Edwards, the British photographer, was again quietly snapping, as he had each Challenge since 2012. Ivan Ronaldson, the marker, had replaced Andrew Lyons, who had marked every Challenge since 2004. Like Lyons, Ronaldson wasn’t afraid of calling chase off—twice in Day Two that was the result of playing off a chase. Per usual, the whole event was orchestrated by Susie Falkner, the chief executive of the International Real Tennis Professionals Association, who had run the Challenges since 2004. Alistair Curley, the emcee for his fourth Challenge but an observer at every Challenge since 1985, got the second day off smoothly at five o’clock.

Lumley was facing a gigantic uphill task. No player had ever lost the first four sets and come back to win. The best model was Tom Pettitt in 1885 at Hampton Court: Pettitt lost three of the four first sets and then the first two sets on the second day before remarkably reeling off six straight sets to capture the Challenge. Lumley’s racquet hinted at his hope of emulating Pettitt. It was a deep blue Gray’s bat, with yellow accents. On one side it read in large letters Peter Latham; on the other Tom Pettitt.

Riviere, on the other hand (literally), was playing with his all-black Wayward. It was a first for real tennis, as it was the fourth brand of bat he had used in a Challenge (Harrow in 2008; Grays in 2014 and 2018 and 2022; and Gold Leaf in 2016).

Racquets in hand, the players came out looking a little worse for the wear. Riviere had a compression wrap on his left knee and Lumley had athletic tape around his right-hand thumb.

With Riviere dashing to a 3-1 lead, it looked a bit one-sided in South Carolinian’s favor. But Lumley clawed back, taking the next three games. He was playing more decisively, cracking balls into the tambour rather than floating drives to the gallery wall. Still, he wasn’t forcing much: just two balls into the dedans and two into the grille versus six dedans, three grilles and one winning gallery for the Riviere. Down 3-4, Riviere blew a 40-0 lead, squandering four game balls before clinching the game. Then Lumley grabbed the next two games in a hurry, getting his first set in the match.

The sixth set: This time Lumley was the one who jumped to a 3-1 lead and then lost it. Riviere ripped off six games in a row, taking the set with relative ease. Lumley wasn’t serving particularly well—sometimes he overhit his railroad and it bounced off the back penthouse and then the side penthouse, giving Riviere an easy volley for length to the main-wall corner; and his second serve, often a demi-pique, was sometimes too long and Riviere was able to turn on it and smack a forehand. Lumley had trouble finishing off games, giving up eight game points. Riviere, as slippery as an eel covered in Vaseline, could not be pinned down in the corners but managed to again and again escape when retrieval looked impossible. The tail of the tape: five grilles and four dedans for Riviere; two of each for Lumley.

After two reasonable sets—each just over thirty-five minutes—it deepened into the heart of the match. Set seven saw incredible tennis, long point after long point, openings just barely missed. Riviere was up 3-1 and 4-2. Lumley then hit three grilles in one game to peg one game back. Riviere took the next to be up 5-3. It wasn’t going smoothly for him, though. His movement was clearly hampered—a stiff knee, a sore hip, something. He wasn’t flying into the corners as much. He was not finishing off games, squandering nine game balls during the set. Riviere had that first-mate-on-the-bridge-after-a-storm look—beleaguered and bedraggled. At 5-4, he slipped onto the floor. The set went to 5-5, fifteen all, tension thick in the air. Then, 30-15 for Lumley and an epic point ensued with superlative shotmaking. And Lumley finished it off to ensure a Day Three. Nine dedans, seven grilles and a winning gallery for Riviere; three grilles and one dedan for Lumley.

The last set looked surely to be Lumley’s. As cool as a north wind in winter, Lumley flew to a 4-0 lead (the first three games took under ten minutes total). That meant he had won seven straight games, a skein of excellence that suggested the set was finished. But not so. Riviere summoned great courage and battled back. He smacked three dedans forces in a single game. The set stretched for well more than an hour. Two amazing games occurred, at 4-3 and 5-4. In both, each player saved multiple game balls (Riviere saved four in each, including blowing a 40-0 lead down 5-4 before taking the game). At one point Riviere slipped again, jamming his foot against the battery wall. Again, an eleventh game. Again roars from the crowd, ululating, clapping, cheering and racquets-like exhortations. During one set point, playing off chase second gallery, Riviere boldly cannoned a drive into last gallery. But Lumley calming clinched the next one. Riviere: five dedans and three grilles; Lumley six grilles.

Unlike the exciting Day Two at Queens five and a half years ago, here the points were much longer, with both players retrieving like mad; probably less strategy and less decisiveness on the serve; and certainly less forcing to the openings. It made for mesmerizing tennis.

Now, after more than six and a half hours of play, the match hangs in the balance.

Photos by Tim Edwards

by James Zug

Day Three

Riviere won 6-5, 6-3.

Riviere won the 2023 World Championship seven sets to two: 6-4, 6-2, 6-3, 6-4, 4-6, 6-3, 5-6, 5-6, 6-5, 6-3

The air-conditioned atmosphere at Westwood Country Club could not possibly mask the tension as Day Three unfolded.

The unofficial odds, emerging across the pond, had tightened considerably. Before Day One, Camden Riviere was 1/10 to win while John Lumley was 33/1; and the Challenge finishing in two days was 8/11. Before Day Three, Lumley was getting 20/1 to win 7-6 and 25/1 to win 7-5. It was even just 33/1 for the match to go to 5-5 in a thirteenth set.

The players came out looking relatively fresh. Lumley initially didn’t have his right thumb taped (he added tape at 2-all in the first set of the day). He still had his collarless shirt. Riviere was wearing his third different pair of sneakers—gray K-Swiss boots accented with pink (perhaps he knew what all cognoscenti know, that pink was the preferred color on any Day Three). Riviere was looking vital and refreshed, despite the various aches and pains, including a nasty blister on his left foot’s big toe—a reminder of the inevitable wear and tear that comes with a Challenge (it recalled last year at Prested and how Rob Fahey’s toenails were coming off under the stress of the Challenge).

The crowd seemingly had shifted a bit towards the champion. There were a few more Westwood faithful, Aiken in full flow and it was louder. They cheered in between a first and second serve. They cheered when Riviere won a point. At the same time, the Lumley cohort, missing some exuberant voices during the first set, were not as emphatic.

Throwing his head up like a war horse at the sound of a bugle, Riviere was buoyed by the support. He yelled “C’mon” after winning key points, he hopped from foot to foot before receiving and he sometimes double fist-pumped, knees bent, looking not dissimilar to Tiger Woods after sinking a crucial putt.

After eight sets, the tactics finally changed. The serving was the same, a steady diet of railroads. Both players served better, although both players faulted more on the first serve. More interestingly, Lumley announced his new intentions toward openings by trying to force on the first point and smacking a ball into the dedans later in the first game. Instead of trying to almost always play the floor, he began to go from A to B without inventing letters in between. He totted up six dedans in the ninth set, more than he had in total on Day Two. Nonetheless, Riviere was naturally adept at fending off balls rocketing towards the netting. After all he had years and years of practice playing Fahey. And even when he let it fly past, it worked out: at one point Lumley forced for the dedans, it crushed into the bandeau and as it sped in the opposite direction Riviere waved his racquet at it and skillfully dropped it for a winner under the grille.

Tactics-wise, Riviere was for the first time content to take gallery chases in order to switch sides and gain the serve. This was new. But necessary: in Day Two, Lumley had served 169 times, while he had served just 124 times.

The ninth set started out with balls flying. A long, eleven-minute game ensued at 1-1. Then from 2-all, Riviere got slight breathing room. He was playing freely, with confidence, crunching balls into the grille (seven in total for the set). A love-game at 3-2 and going up 30-0 at 4-2. Then some unforced errors, a few incredible gets by Lumley on balls that seemed dead to rights and his lead disappeared. At 4-4, he had trouble finishing off the game, but on his third game ball he got it.

The ninth set was clearly key. The galleries believed that whoever captured the set would in all likelihood take the entire match. Riviere squandered two set points at 5-4 as Lumley recovered to take the game by crunching a service return off a loose railroad straight into the dedans.

5-5. The third 5-5 set in a row, something all but unheard of in a Challenge. Four points finished in a minute. After slowing down his railroad, Riviere won the first point with a wraparound tambour. Two points in a row, Lumley crushed a return towards the dedans and Riviere stopped it but couldn’t get it back over the net. Another Riviere volley off a Lumley return and it was 30-30. Lumley forced again for the dedans off the next railroad; Riviere volleyed it back but gave Lumley an opportunity for a gallery. Then Lumley got chase two.

Switching sides. Lumley earned his first set point after a nifty volley into the tambour. Chase two—pretty impregnable. Riviere, ever bold, volleyed Lumley’s railroad, with his two-handed backhand (both players often did that with their backhand volleys), cutting it towards the main wall and Lumley couldn’t get it back. Amazing. Lumley got a second set point right away. Chase worse than two. Switching sides.

Lumley couldn’t get enough cut on his return and lost the chase by a wide margin. Lumley then laid down two chase, last gallery and three yards. Lumley flicked a backhand into the grille: thus a third set point, serving, and chase three yards.

Again, just like a few minutes before: Riviere volleyed Lumley’s railroad crosscourt and Lumley couldn’t dig it out, Riviere beating the chase, but barely, at worse than two. Extraordinary.

Riviere got a nick for a chase, and advantage when one of his floating backhands hugged the gallery wall. But on Riviere’s first set point, playing off chase three, Lumley peppered his backhand, hitting the ball six times, and then calmly stroked a ball too tight on the main wall. Extraordinary again.

The third deuce. Riviere pumped a volley into the grille. Then he did it again. And the ninth set was suddenly his. It was a magical moment at the end of a magical, fifty-minute set.

The tenth set. Lumley could have succumbed after the deflating end of the previous set. Instead, he fought on. Riviere dashed to a 3-1 lead, but Lumley bravely battled it back to 3-3. Riviere hit a behind-the-back ball at one point. It took twelve minutes to decide the sixth game, but it went, after both had game balls, to Lumley

Finally, it flowed for Riviere. An at-love game. The end in sight. Saving game balls at 4-3. At 5-3, Riviere, playing off a chase of two and three, lost the point. It would be the last one he would lose of the championship. At 40-15, they switched sides. Lumley, defending a chase of better than two, hit a poor railroad that came off the penthouses. Per usual, Riviere smacked his two-handed backhand volley crosscourt, and Lumley couldn’t dig it out. Riviere collapsed to the ground at hazard a yard, splayed out, this third title finally in hand.

The summit of Everest is marine limestone. That is a perfect sentence. Camden Riviere is world champion. That is another.