by George Bell

Editor’s Note: In this month’s edition, George Bell writes about the 1980 USA Van Alen tour of England, including our defeat at the hands of the English team in the featured match. It is said that the winners write history, but sometimes the losers have the better stories.

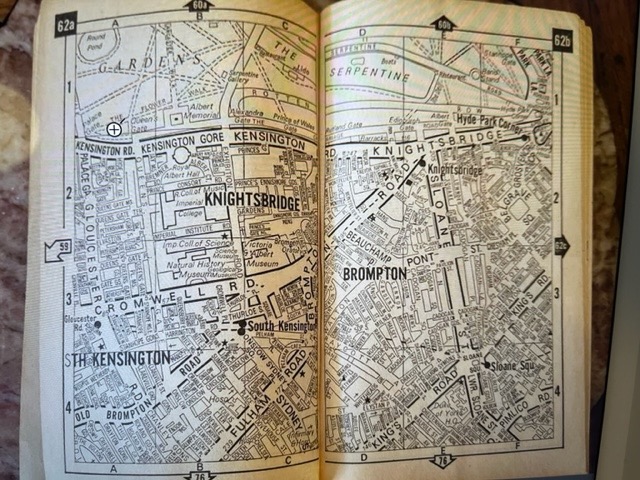

Pictured above is a page from the A to Z London Guide.

In the summer of 1980, the Van Alen Cup team played an away game that stretched over two weeks and a dozen courts in the UK, culminating in the Cup matches at Queens in London. The hardest part of the trip was navigation. The London A-Z Street Atlas was best-in-class and cost 85p (about $1.50). The thicker UK version, another 85p, provided street maps outside the City of London, which would guide us to Hayling Island, our southernmost court, and Falkland Palace in Scotland, our northernmost court. Each was the size of a small phone book, another navigational aid that has gone the way of the Dodo. The two guides were given to me by Alan Lovell, our trip organizer on the UK side, a classics major at Oxford and a rising star in the game. Our kick-off meeting took place at his office, or at world champion Howard Angus’ house, none of us can quite remember. Also Alan presented us with a single copy of a paper itinerary, indicating what court we needed to be at, on what day, and a single contact phone number for the captain at each location. If anything were to go wrong, Alan admonished, we were simply to drive to the nearest village, find a phone booth, obtain a few pounds in coins at the nearest News Agent, pump the coins into the phone box and call the appropriate capitan. We were learning that Alan could be intimidating, largely because he took our competence for granted. He emphasized that it was important not to lose the itinerary, as we needed to be at a new court every other day, matches and dinners had been organized, etc. Then he handed us the keys to a rented, lime-green Vauxhall mini-wagon, reminded us that the wheel was on the right side, and wished us the best of luck over the next two weeks. None of us – my teammates Peter Vogt, Jimmy Knott and Steve Loughran – had ever driven in the UK, ever used a foreign street atlas, and, as feckless young men of the era, would rather give up our pot stash than ask directions of anyone.

It was a time of transitions at home. Vietnam was behind us; a muted vibe of anti-establishment rebellion still crackled through our radios but less angrily. We went from Jimi Hendrix to Prince. Early in 1980, the Miracle on Ice at the Lake Placid Winter Olympics added to our sense that America could do anything, then John Lennon was killed at the end of the year. Fashion got its wires crossed and for a time mullet haircuts, tight shirts with big collars and spandex running shorts were cool. A portable tape player, the Sony Walkman, made its debut. Ronald Reagan would defeat Jimmy Carter that year, with his cowboy ethos and Morning in America mantra, promising to shrink both government and taxes. Our court tennis clubs were still very much men only. In the UK, we were expected to wear coat-and-tie to all our match dinners and make a toast of gratitude at each venue. Each of us brought along one blazer – should do it for two weeks. None of us had a pen, nor did we see the need for one, but that could be pretty easily solved. After all, I went to Harvard; Vogt went to Princeton; Loughran was still at Princeton; and Knott, when asked, would say he went to the University of Hawaii at Maui.

Jimmy Van Alen Cup started the eponymously named event in 1956, based on the Prentice Cup format in lawn tennis – a biannual competition comprising four-man teams that would square off with four singles matches and two doubles. In case of a 3-3 draw, a doubles match, made up of a new pairing, would break the tie. In a stealthy way, the Van Alen Cup functioned as a junior development program. Camden Riviera and Barney Tanfield participated as youngsters. Steve Loughran, the fourth ranked player on our squad, had barely played court tennis when we arrived in London and finished the tour as possibly our second best player. Loughran would go on to captain both the golf and squash teams at Princeton his senior year.

The Vauxhall was our home and locker room on wheels with all our sweaty gear in the back and four healthy lads chatting away. Especially in the countryside, where traffic was thin, we often drifted to the wrong side of the narrow roads, so badly in fact, that a few times after near collisions, we had to pull over to marvel that we were still alive, stroking our arms in nervous gratitude. We sang to the radio. We dubbed ourselves the Singing Swordsmen, crooners as well as, in our minds, such precise ball strikers that the ball sang off our strings. Maybe a week into the tour, under a beautiful twilight sky in Scotland, I came into a blind hairpin turn a little hot and needed to guide the Vauxhall into a ditch to avoid tossing roadside sheep into the air like so many bowling pins. Their herder was shaken and unhappy, which was nothing compared to Loughran, who had been simmering for days in the back seat with fear and outrage at my driving. “That’s it!” he said, getting out, slamming his door and walking around to examine the badly creased front bumper. Steve was the youngest and shiest of our team. He was terrified. Secretly, I felt proud to be bringing him out of his shell. I had many other bonding experiences with Steve, too.

Just when we had calmed down and realized that we could still drive the car, and the herder had gathered his sheep, the itinerary disappeared. In the melee it had vanished. After removing all our gear from the car, our empty food cartons and cups, and old, discarded grips like peeled potato skins (we often re-gripped our racquets in transit), a corner of the itinerary appeared, poking out from underneath the back seat. Then we put everything, including the trash and moldy grips, back into the car and continued on.

At our match against the team from Morten Morrell we had the rarest of galleries – one that contained a young, beautiful woman. Peter Vogt reminds me that Knott and myself were starved for female attention and wanted to improve our odds of being noticed. We conspired to tell this woman that the Choate emblem on Peter’s shirt represented, in the US, an infectious disease that you were required to warn others about when you were in public. Then Knott told her about his years at the University of Hawaii at Maui.

We got stuck at the pub with the Danby brothers at Hayling Island and nearly had to spend the night on cots above the bar. In Leamington, we played tennis on Charles Ward’s grass court, where Vogt barreled toward a short volley, tripped, took the net down and one of its wooden posts as well. We had a silvery night at Troon, with a northern summer sky and an outdoor black-tie party in our honor (we all borrowed bow ties), where Knott and I got a crush on our hostess, Char Tulloch. We learned how to read the diabolical AZ street atlas, where every page pointed to another map on another page, causing my co-pilot, usually Knott, to shout sudden changes in direction, Right! No, no left, I mean left!” We learned how to push coins into a pay phone slot rapidly enough to keep a phone call going, when we needed to report that we were utterly lost or running late. We had a lovely match at Manchester until Knott, who volunteered to give our toast of gratitude at dinner, raised his glass to Britain, “The 51st state.”

The U.S. side were perennial losers in the Van Alen Cup, mostly owing to our late start in the game. Cambridge and Oxford have their own courts and teams; many players become active in their mid-teens. Here we have no college court tennis teams. For decades, our clubs discouraged “children” and frowned upon any young man who had not yet turned 21. Players that later played wonderfully – Van Alens, Bostwicks, Vehslages – struggled in the Van Alen Cup.

I played in the ‘78 Van Alen Cup in Philadelphia and we got crushed. I recall that Jimmy Dunn, who shepherded three of our four team members for the 1980 campaign, had the insight that we could win because we knew doubles better than the Brits. For some reason this gave us confidence. He suggested that Peter Vogt captain our team. At the culmination of our trip, in the Van Alen Cup at Queens, we won both doubles (Dunn was right) and went down 3-0 in singles. We needed to win the last singles match to eke out a tie. In the number one slot, I prevailed over William Hollington 3-2 in sets. With the match now tied, Vogt put up Jimmy Knott and myself as the team to play the tie breaking doubles. We went ahead 2-0 in sets. Sensibly, Vogt and Loughran retired to the Queens bar to select the champagne. We managed to lose the next 3 sets in painful, high-speed fashion, as can happen only in court tennis. (Though in my mind I chalk it up to playing ten sets on that final afternoon). At least we scared the Brits and put them on notice that the US teams were improving.

Only later, when we came out of the haze of being in our early 20s, did we think to ask: who paid for the Vauxhall repair? Or Charles Ward’s new tennis post? Who paid for our trip, for that matter? In two weeks, did we ever do any laundry? Why did every court receive us so warmly? Did we return the A-Z guides to Alan Lovell, or burn them? We knew nothing of gratitude, and even less of the cocoon of generosity that we lived in. Maybe that’s what the Van Alen Cup was about, after all, the simple idea that goodwill begets goodwill, and each of us, by the end of that summer somehow understood that a new responsibility had fallen on us too.

The author welcomes all comments; email George Bell at bell.george@gmail.com

To learn more about the Van Alen & Clothier Cups, read Jim Zug’s story in the 2008/09 USCTA Annual Report “Junior Tennis on the Rise”