by George Bell

Jimmy Burke’s career in court tennis began when he was 14, mopping and scrubbing the floors of squash courts at the Racquet Club of Philadelphia, and came to an end 44 years later in Boston, where he had served as the head professional for many years. Along the way, he worked at four different clubs, won countless tournaments and challenged for the world championship in 1977. But his identity is not court tennis or less so than you might think. Instead, a constriction of misfortunes shaped him and seemed, over decades, to cling to him like a childhood curse. And yet, most of my interview with Burke was punctuated with laughter.

Jimmy’s short gray hair spikes straight up. He reads as a retired lightweight boxer with an intense gaze as he points to his knees and hips with a giggle, mapping all the joints he’s had replaced. I asked if we could meet at the T&R in Boston and he’s taken the ferry up from his home in Hingham. Jimmy is a stranger now in the place he labored for so many years. Most people at the club don’t know him but there were happy embraces from older members and staff. Jimmy, 66, brought a smile to their faces. As we walked behind the dedans to the Hamlen room, a quiet place to talk, you could see that he still had the looseness of an athlete in his limbs. Even when Jimmy sits he’s in motion, moving around the confines of a chair as if something were bothering him.

His father was a milkman who commuted daily from their row house in the Philadelphia neighborhood of East Falls, over the Benjamin Franklin Bridge to Camden, where milk was still delivered door-to-door on the best streets. When Jimmy was four, his mother was quarantined in a facility for several years with tuberculosis, not an uncommon strategy in the early ‘60s. “My dad would tell me to get down on the floor of the back seat and throw an Afgan over me, to sneak me in to see my mom maybe once a month on a weekend when he had time to drive me. I missed her terribly” he said, clenching the chair arms.

In their house on Eveline St., the six Burke kids shared two rooms. With no mother at home, the oldest of the four sisters was in charge and thought nothing of locking Jimmy in a closet after school when her boyfriend came over. “It took me a long time to understand that I was abused as a little kid,” he says, his voice going quiet. “I was very active and needed to move, I used to kick at that door over and over. I needed to get out.”

Back then, East Falls was autobody shops, diners with swivel counter seats, and discount appliances in the window of the hardware store. Everyone knew everyone. Bars and churches and schools and playgrounds, but if someone wanted to break away, Jimmy would hear his sisters say, “Who are you trying to be, leaving East Falls?” Still, East Falls was also a breeding ground for court tennis pros because the legendary RCOP head pro, Jimmy Dunn, came from there, hired from there, and believed it was a good system. Assistant pro, Tommy Walsh, offered Jimmy his first job – $27.50 a week and $1 for marking a match. He had never seen a court tennis court. Before he could get on the court, he spent a year learning to string racquets, cut cloth and bind balls after school. He had to memorize the names of members and remember to call them mister. He was terrified of Jimmy Dunn. But the job was just a short train ride from East Falls, a world apart from his family, and he would have his own money.

Jimmy struggled with reading but he excelled at sports. Soon he began to go into the court right after school when it was quiet, empty. He hit balls by himself for months. It was hypnotic. “I loved it,” Jimmy said, “it was so strange and new.” One day, Dunn turned the corner from the pro shop, walked down the red-carpeted hallway and simply began to instruct Jimmy. “He never came around the corner,” Jimmy remembered. But that’s when Jimmy knew he must have talent. Secretly, he also believed he reminded Dunn of himself when he was also a teenager from East Falls who had been given a break.

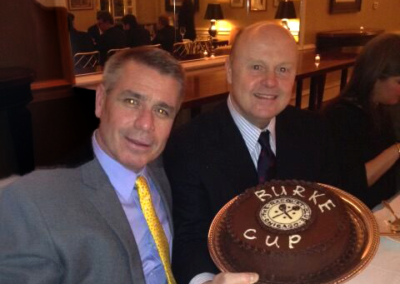

While holding down his growing duties at RCOP, Jimmy went on to win the US Open singles and doubles. He was a three-time winner of the US Pro event, defeating stars such as Barry Toates, Lachie Deuchar and Chris Ronaldson along the way. “My memory is pretty bad,” he smiles. “Some of it, sure, but less than you think I would.” He earned a challenge for the World Championship in 1977, traveling to Hampton Court to play Chris Ronaldson on his home court – the winner of that contest would meet Howard Angus, then the defending world champion. What stands out for Jimmy is he never prepared properly. He should have come to England earlier, given himself more time to get acclimatized, and understood the quite large court better than he did. He flew to London only four days before his match, hampered by Dunn’s desire to keep him in Philly, and his own ignorance of how to prepare well. He had no sparring partners and no one to tell him how to develop a strategy for Ronaldson.

But ask him to compare the two worlds he found himself living in as a teenager, and he moves forward to the edge of his seat with excitement. “Let me tell you, there was this huge black guy at school, at Roman Catholic High, who took my lunch money, $1.50, every day one week, by threatening to beat the shit out of me. I was a really good fighter, very scrappy, very tough for my size.” Then Jimmy leans back in his chair as if struck by a wind. “Let’s face it, this guy was going to kill me. But on Friday that week, I told him no more. I didn’t give him my lunch money. He told me to meet him outside behind the school at the end of the day. I knew I had to fight him, it was the only way to show him he couldn’t push me around. Sure enough, after school, he beat the living shit out of me. But I got in a couple of good licks and I bit him in the stomach clean through the skin. The guy never came after me again. When I got to the Racquet Club, my tie was ripped, and I was badly bloodied with two black eyes. Jimmy Dunn looked at me and said, ‘I guess you came out on the wrong end of that one.’ ”

Of course, there was only one way a kid like Jimmy Burke would find a path into a place like the RCOP – he had to come from East Falls. And yet for Burke, East Falls has also been a source of pain, bad habits and heartache.

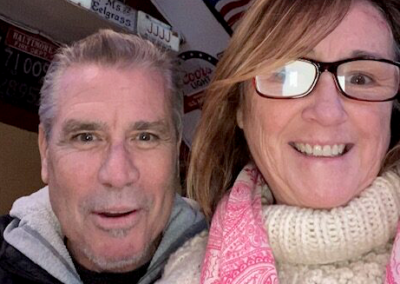

Court tennis didn’t prove to be a perfect way for Jimmy to leave behind all his troubles. Some of them followed him, some he made for himself. He talks about the chaos of the ‘80s in his personal life. He fathered a son, Dustan, with a girlfriend. There was drinking and more, and falling out of favor in the court tennis world. It was NYR&T pro and world-champion Wayne Davies who gave him a break to start in New York in 1983, after a dozen years at RCOP, but that didn’t last as long as he had hoped. Devy Hamlen gave him another break, and soon he found himself in Boston, and another chance at redemption. He reconciled with Dustan’s mom – mother and son moved to Boston to give it another try with Burke. They had a second child, Samantha, but the reconciliation was short-lived. In the autumn of 1998, he met Brenda Murphy, who worked in member marketing at the T&R where Jimmy was already the established head pro. “I swear to you,” Jimmy says, both hands raised over his head, “Brenda really helped me, and I really started to get my act together. In a more permanent way.” They married in 2001, as Jimmy churned out his last, long run at the T&R.

Black Rock Country Club in Hingham boasts a Brian Sliva-designed 18-hole golf course on the grounds of a 100-year-old quarry. It’s a family club, with a large swimming pool, a tennis complex and several restaurants. Fixing divots on the tee boxes and keeping the surrounding areas in pristine shape has been Burke’s work on the grounds crew for the last seven years. “I love being outdoors, I love the activity, and the camaraderie with the crew,” he says, leaning forward again, running his hand through his hair. “I can only do three days a week now, my knees can’t take more than that.” He giggles and rubs his hands together, adding, “I remember a doc said to me once, years ago, whatever it is you’re doing all day, get out of that biz before you become a cripple.”

These days, Jimmy rides his bike everywhere, even to work at the golf course. He does sit-ups and lifts light weights at home. “I gotta stay active,” he says, “it’s just me.” He has five grandchildren, some from Brenda’s first marriage, who are an integral part of his days.

His style as a player was very much blue-collar East Falls: a counter-puncher, maybe one of the greatest retrievers the game has seen. The nightmare opponent who wouldn’t quit. He was severe with the cut on his forehand, bending so low that his knee often scrapped the floor. He didn’t have the size to become a banger or rely on forces to the openings. But his competitive spirit was pugilistic, unrelenting. He’s unbothered by the fact that he can’t recall the dates of his highest achievements in the game – the fight was the thing. If he had a chance to bite you in the stomach, he was going to break skin.

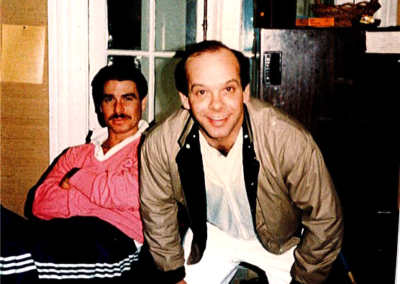

I grew up in Philly and mostly my introduction to the game came at RCOP, through Jimmy Dunn and Burke, who became a good friend to me. We got up to a lot of stuff that is probably best left out of this profile, but Jimmy knew how to have fun. He knew how to rig the windows before the guys locked up the “Turkish” on a winter evening so we could climb down the outdoor fire escape in nothing but our towels, pry open the window to the pool and steam room and enjoy the whole area in private. Jimmy had a number of other “guests” whom he introduced to the club in that way, explaining to at least one innocent girl from East Falls that the club was actually Jimmy’s family mansion. He was charm and grit in equal measures.

Misfortunes – the blight of strained relationships, addictions, run-ins with the cops, and jail – piled up over the decades within Burke’s family and their circle of close friends. Sometimes bad luck, sometimes self-inflicted wounds. Jimmy lost his only brother three years ago to an overdose. “You know,” he shrugs, “that’s still what’s going on in East Falls.” He still struggles with some of his family relationships back in East Falls, maybe because none of the sisters left there, or because he left.

It’s grown dark outside and Jimmy has to catch his ferry back to Hingham. I’ve loved seeing him again, and I reflect that I have a bias in his favor; I’m still rooting for him. The thought reminds me to ask him how in the world he’s remained so positive. He looks at me without hesitation, and says, “George, my mother and father loved me. Through all the f’ed-up stuff, I always knew they did.”

On court – the court that Jimmy presided over for many years – a young man instructs presumably his girlfriend, on the hazard side. She’s clearly a beginner. As we get ready to go downstairs, Jimmy watches for a minute or two, grabs the netting of the dedan with both hands and shouts to her, “Don’t use your wrist so much, less wrist!” She actually accepts the tip, from this stranger in the gallery, and Jimmy watches as she swings at a few more forehands. “That’s it,” he says. He turns to me, shrugging through his impish laughter, and adds,” I can’t help it, I’d like to see her get better.”

Comments: bell.george@gmail.com