THE SOLDIER

A RECOLLECTION OF JIMMY KNOTT

by George Bell

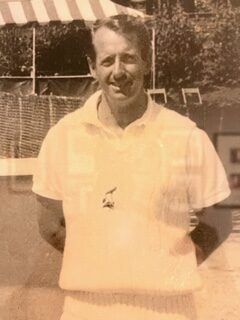

He was stocky, feral in his gait, wild-eyed with one brow often arched as he strode down the third-floor hallway of the R&T on his way to the locker room. But he was dapper too, arrayed with his pocket square and regimental tie and doubled-breasted blazer and gold buttons. He honored the club’s dress code, even in his early 20s, while most of us came through the backdoor without a tie and rode up the service elevator. With his long face and prominent nose, he resembled a French nobleman. Jimmy was always excited to play – racquets, most beloved, and court tennis and squash, often on the same day. He was entranced by history and war and codes of behavior. In his childhood, he amassed a collection of painted tin soldiers, which he arranged on the floor of his bedroom to re-enact famous battles.

Jimmy was born into New York and R&T royalty. His great-grandfather founded Knott Hotels in 1889. The chain grew to 40 properties. Their jewel, the Westbury Hotel, was acquired from the Phipps family in 1953. Oversight of Knott Hotels passed dutifully through the chain of generations to Jimmy’s father, Jimmy Knott Sr., who chaired the company until its sale to Trust House Forte Ltd. in 1977. Jimmy’s half-sister was Lilias Knott Bostwick, who married Pete Bostwick. Also, Jimmy had Whitneys and Cushings in his family tree.

At the outset, Jimmy’s education followed a well-worn path if you grew up lucky in Locust Valley: Greenvale School followed by boarding at St. Pauls, where he overlapped his nephew Pete Bostwick and niece Cackie Bostwick (“Uncle” Jimmy Knott being roughly the same age as Pete and Cackie.). Afterward, he went to Univ. of Minnesota and then the Marine Corps., where he rose to the rank of Captain. His largely self-taught knowledge of military history, and British respect for order, were welcomed. There was something recalcitrant about him, too, a distaste for authority, as there often is at the heart of those who enlist. He loved to hunt birds, ski the backcountry of Colorado, and fly fish in great rivers in the US and UK.

He later married a wonderful Scottish woman, Susan Frances Gordon; they had two children, Adelaide, named after Jimmy’s mother, and Iain. It was in saving Iain’s young life that Jimmy lost his. With Iain in his lap on a June day in 1995, father and son rode atop a tractor on Jimmy’s new farm in the Amish country of Pennsylvania. At some point, it became clear that the tractor would tip over, and there was no avoiding disaster. Jimmy threw Iain from the tumbling machine to save him and was himself crushed beneath it. Two days after his 40th birthday, Jimmy was dead.

In the summer of 1980, the Van Alen Cup team headed to England with nine courts on our agenda, including the roofless Falkland Palace in Scotland. A small lime-green Vauxhall wagon had been rented for us with a sponsor’s name affixed to the driver’s door. Our roles weren’t the subject of an election, but somehow we fell into them: I drove for ten days while Jimmy and Peter Vogt took turns as navigators. Steve Loughlin, the youngest member of the team and least experience at court tennis, preferred the back seat, a better place to contain his terror as we navigated single-land roads through villages and hedges that looked like tunnels. That first week we dodged sheep and deer and often found ourselves on the wrong side of the road. Jimmy was the only one to encourage me to go faster. The four of us spent many hours in the car, with our gear growing riper by the day. Jimmy filled our driving hours with British battle history and trivia about arcane British field sports. Lords, Hayling Island, Moreton Morrell, Oxford, Cambridge – every day, a new court, a new match, a new place to sleep. We were young, and we loved it.

At night, Jimmy and I shared a room. He always asked our hosts for a small Scotch after dinner. One summer evening at Troon, we were invited to an outdoor black-tie dinner, the Scottish light silver and shimmering even at 10 o’clock. We both fell in love with our hostess, Ian Tulloch’s wife (was her name Char?), 15 years our elder and the mother of two infants. The next day, when we returned to the Tulloch’s after our matches, we were told we could use the bath on the third floor to wash up and that it was already drawn for us. We were to let the water out only after we had finished. Ascending the narrow stairs, Jimmy and I saw that other members of the family had already used the bath water. Peering at the surface, milky with soap, Jimmy said to me, “Well, if it’s OK for Char, it’s OK for me!” and roared at his own joke.

We won the Van Alen Cup in a tight battle at Queens that June. Jimmy was a leftie and my partner in the doubles portion of the event. He played the green line. He was gritty and strategic. For every match, he wore a classic cable-stitch sweater. But the most outstanding Jimmy Knott moment came earlier in the tour when we stopped for a match and dinner in Manchester. It was grim and dark and had no wild feeling of the Scottish summer to the north. We drank impressively. At the end of the evening, we continued our tradition of giving a toast of thanks to our hosts. Jimmy turned to me and said, “I’ll handle the toast tonight; I have a good one,” his eyes, wild and severe, began to dance with mischief. Soon he stood, glass raised, in a room thick with cigar smoke and proud British gentlemen, and with a nod of thanks and a suddenly solemn voice, he intoned, “Here’s to Britain…the 51st state!” He alone cackled with laughter, easily heard as the rest of the room was reduced to an uncomfortable silence.

The Jimmy Knott tournament occurs early in the court tennis season because Jimmy was an early starter. He trained and was always prepared. You must take a year off if you win it because Jimmy believed in true competition. He abhorred bullies. When he was on the court – with its restrictions and strange rules, he once said to me that he felt a sense of freedom. That was very Jimmy, placing conformity and freedom side by side. You will see none of this written in the tournament description, but I think it’s what Jimmy would want us to remember about him as a player and a sportsman. The Jimmy Knott Singles commemorates his tragic end, his spirit of joy in our game, and perhaps most of all, his embrace of camaraderie. May we not forget him.