by George Bell

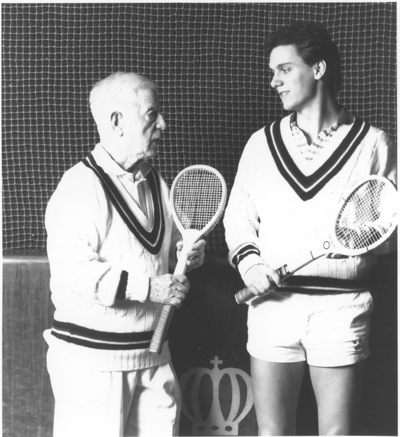

A lesson with Jimmy Dunn 45 years ago was nothing like a lesson today. The legendary Racquet Club of Philadelphia head pro entered the court in sneakers, gray flannels, and a white sleeveless sweater, a small man with the arms of a blacksmith, usually with a cigarette hanging from his mouth. He didn’t look you in the eye and had no memory for names. You were summoned to the dedans with a jerk of his square head. “Let me see you cut a forehand,” he would growl, his racquet tucked under his armpit. Already he had an impatient, withering look. After two strokes, he would say “for chrissake” in disgust, the cigarette flapping on his lip. Then it would get worse.

East Falls, an Irish Catholic neighborhood seven miles northeast of Philadelphia, is dense with brick row houses and the sound of Philly accents as people yell to each across the way, parked cars lining both sides of the streets. Autumn nights with tavern-goers drinking on the sidewalk and summers spent on the porch, listening to the Phillies game on the radio. Jimmy Dunn territory. Folks were blue-collar, reticent, gruff, and full of quips. They were church-going sports fanatics who stuck to themselves and were preternaturally wary of outsiders. Somehow, Jock Soutar, a man of Protestant breeding and RCOP’s head pro through WWI, found and recruited Dunn as an apprentice. Dunn dropped out of North Catholic high at 14 years old, and that was the last of his education. Well, school education, that is. The year was 1928. Jimmy was short, red-headed, and a lefty. He took the trolley to the club, whose great Georgian facade must have looked to him like a walled palace. He entered by the back service door to begin the only job he would ever have, serving 59 years, rising to head pro for all racquet sports, with a short leave to serve in WWII.

Dunn learned quickly. Over many years he won 31 national championships in squash, court tennis, and racquets. But he remained the outsider, the man from the servant caste, who carried a bit of an edge at a time when class distinctions were drawn as neatly as street addresses on granite curbs. He was savvy enough to realize his path to respectability among the membership was through his achievement on the courts. Winning trumped breeding. When in 1964 Dunn won the US Open with club member Bill Vogt, the NYT ran an eight-paragraph story about the finals, observing, “Dunn, at 50 years the oldest man on the court, played one of the most brilliant matches of his career, and was easily the outstanding player during the 1-hour 50-minute contest.” He became perhaps the best doubles coach of the 20th century; his wisdom won him a kind of camaraderie and respect beyond his own victories.

The story could end here, I suppose the under-sized kid from a tough neighborhood who gets dropped into a world of arcane sports and private clubs. A blue-collar man in a black-tie game who carves out a long career for himself on his own stubborn terms. But that would leave out the miracle – Dunn’s remarkable, unlikely legacy that continues to enrich our game almost a hundred years after he first walked through that service entrance.

Jimmy soon realized that his humble background and hardscrabble neighborhood of East Falls could be a source of court tennis apprentices who would be loyal to him. They would owe him, and they would work hard. He started with his nephew, Jimmy McCaffery, but he needed more recruits. When he stopped in for a beer at Falls Tavern on Indian Queens Lane, he asked about talented neighborhood kids. The local railroad station master referred him to Tommy Greevy, who dropped out of high school and quit his weekend job at the butcher shop to become a Dunn apprentice. On Sundays, he asked around at church. Not all the kids worked out; some were overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the club or intimidated by the membership. He hired Tom Anthony Venetta from Tilden St. but called him Tony as he didn’t want two Tommys working in the shop at the same time. Dunn’s budget called for three apprentices during the busy winters. He found Bernie Elero from Crawford St. and then a kid known only as Two Shoes, who didn’t last long. Word of mouth created a steady flow of young, athletic men from East Falls: they learned to handle court bookings, string racquets, mark a match, address everyone as mister, and maybe become proficient at “the games.”

After years of this, East Falls became the only blue-collar neighborhood in America where many people knew a chase or a hazard; kids at Roman Catholic high could explain the tambour, and mothers could describe the dedans though they had never seen one. And there was pride. Soon Dunn found Ed Noll, from Ridge Ave., whose mother, Mildred, sewed balls for the ‘73 US Open singles tournament. Another Tommy followed – Tom Welsh – from Eveline St., whose mother also sewed balls. Then Dunn found Jimmy Burke, who was challenged for the world championship and grew into possibly the best retriever our game has known. Even Mike Noll was recruited… by his dad Eddie, who had become the head pro and later the club’s general manager. There was Tom Brill, too, from Baldwin St., Tommy Greevy’s godson. Mark Licorobic stayed only a few winters and later became a PA state police officer. Later came John Cashman, who lived on the same street as the Welsh family. And, of course, Robbie Whitehouse, a nephew of the late Ed Noll and a product of East Falls, who started when he was 17 and is RCOP’s current head professional. Some of these pros are too young to have met Dunn, who died in 1989, but they know the stories and are each a part of the legacy.

Over the decades, Jimmy Dunn never changed. He treated all of his apprentices the same, calling each one “kid” and motivating them by declaring from time to time that each was “the dumbest effing person I’ve ever met.” They called him “Dunny” and rolled their eyes. He hated New York and what he saw as the pretensions of the R&T. He viewed the Whitney Cup as the peak event of the season, the chance to prove that underdogs mattered.

At one time or another, East Falls supplied the men who grew into court tennis professionals in Philadelphia, New York, Tuxedo, Boston, Chicago, and Newport. Over a dozen players from East Falls played in the US Open over a ten-year period. In other words, Jimmy Dunn created and supervised the greatest player development program in the history of our game.

In his last years, he liked to read the paper in the morning in the pro shop with his coffee. He didn’t answer the phone. He held grudges, objected when players started to put grips on their racquets, and deliberately warped the racquets (by taking them in the shower with him at the end of the day) of members he didn’t like so they’d have to buy new ones. He never forgave me for not settling back in Philadelphia after college in the early 80s. “You could have helped us win a few more Whitneys, you know,” he said when I played at the club over Christmas break. He was still smoking, his face a worn-out catcher’s mitt, staring through the dedans. “Your grandfather (John Bell, who played with Jimmy at the club in the 1930s) wouldn’t be happy about this,” he would add, playing the family card, not looking up from the ground. That was Jimmy – honest, protective, and unconcerned about how people viewed him.

Dunn died at 75, leaving 12 grandchildren and more than 20 court tennis apprentices, or should we say, graduates. He had become the thing he least expected – a welcome presence in a world he both disdained and cherished.

In his old-fashioned way, he once described the process of improvement: “The point is that the better you play, the more pleasure you get out of it. No matter what you do in life, you only get out the pop you put in.”

George Bell – bell.george@gmail.com