by George Bell

On a Sunday morning in January, I turned off a major roadway in Manhasset, NY and entered Greentree, an estate marked by a modest, painted sign that you could easily miss. Malls and car dealerships had displaced the Gold Coast mansions long ago, but not this one. Hemmed in by the neon of another century, Greentree had defied the odds, frozen the clocks. The quiet was immediate. The property’s entrance road gave passage to a forgotten world, where great stretches of cold, blue light lay across an inch of new snow.

The security guard stepped out of his warming hut but when he saw my face, or perhaps that I was dressed in whites, he waved me through with his clipboard. A first. I had come to play court tennis on enough weekends that he recognized me. Though the roads of the estate, branching here and there, were already plowed, you drove slowly as it seemed the right thing to do, the black asphalt ribboning over hills and past fenced paddocks like a series of connected questions. The Whitney’s 400-acre property stretched to the horizon on all sides, holding fifteen or twenty houses, each conforming to an exacting aesthetic — lanterns and driveways and bluestone walkways — bordered with boxwood hedges, rhododendron, and slumbering fruit trees whose bare, elbowed branches were black and still. Here and there stables, storage sheds, repair shops. The finish of each structure — shingled and painted dove gray, trimmed in Greentree green and white — conveyed security and order. Everything could be done here, taken care of, fixed. Yet I almost never saw anyone, hundreds of windows across the estate dark and unoccupied, as if all was maintained for the benefit of ghosts.

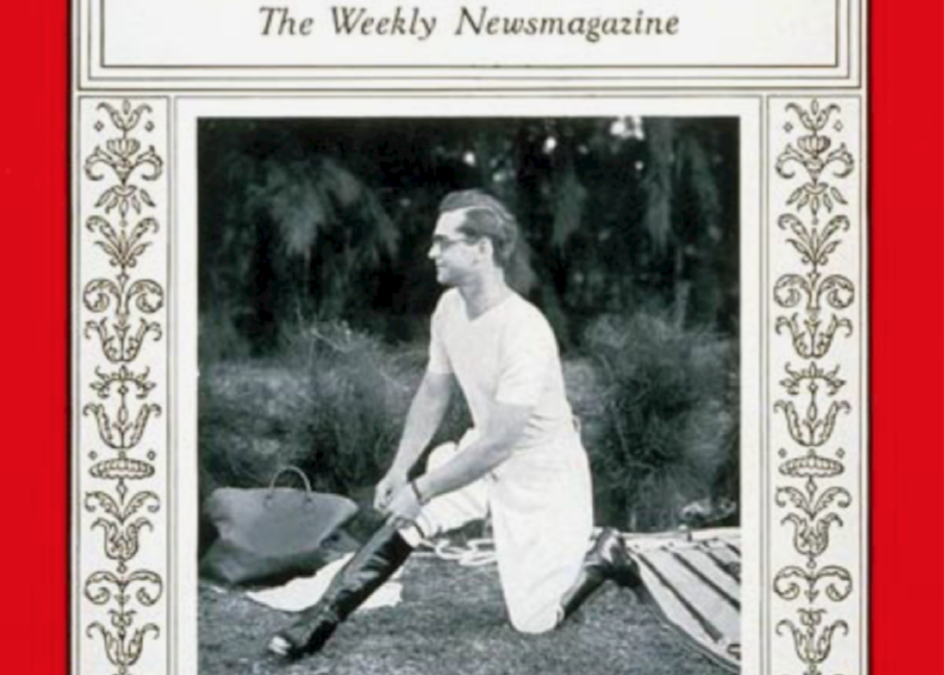

There was an idea behind this, a thought-out plan. The property was an amalgamation of five farms, put together under the direction of Payne Whitey in 1904 and passed down to his descendants. His son, John Hay “Jock” Whitney enjoyed enormous financial success and was credited, along with his partner Beno Schmidt, with developing venture capital as a new line of business. Their biggest scores were in film and media, and in the company that developed Minute Maid orange juice. At his peak, Whitney was ranked the tenth richest American and appeared on the cover of TIME. He was also a sportsman, best known for his skill with horses, and of course court tennis. Looking out on rolling hills and pastures, I stopped the car to watch blanketed horses, still as statues, nose the grassy stubble poking up through the snow, wondering how much of this I would remember later in my life. Once inside the estate, it took only a minute to feel separated from your cares and elevated to a higher purpose. I promised myself to be a kinder husband, to read more, to do charitable works. My God, how this property could alter you. When it could get no better, the wet road turned and revealed a huge jewel in the winter sun, the surpassingly beautiful main house and the court tennis building appended to it. An hour of doubles lay ahead in this setting of wonder. It was 1994, four years before the death of Betsey Whitney, Jock’s widow around whom the entire estate turned, kept up for her as it might have been some 90 years earlier. And it was to be my last game on that court.

Many of our best tournaments are place-based, fixtures as the Brits have it, a court and an event intertwined: the Gold Racquet at Tuxedo, the Jimmy Dunn at Philadelphia, the Silver Racquet at the R&T. It’s odd that the Whitney Cup, our communal tournament, the one that generates the most competitive heat and chatter, is an orphaned event, dislocated from its iconic court. The Payne-Whitney Intercity Doubles Championship was first played at the R&T for two years, then moved to Greentree in 1933, where it would be played for 67 years, (with a two-year hiccup in the ‘70s due to Jock Whitney’s brief illness), before returning to the R&T. The Greentree estate gave Whitney its character. We played as guests of the Whitney’s, and you never forgot that you were a visitor in someone’s home. Sportsmanship and camaraderie prevailed — they better have or there was no return invitation. The Whitney’s also opened the court to a small handful of players on weekend mornings in the winters.

Jack Hickey, the renowned weekend marker, worked part-time at Greentree for over 25 years, stitching balls, stringing racquets and supervising the court. The son of Irish immigrants, he was a veteran of the pro shops at the Racquet and Tennis, and University Club in NY. He knew our games and people, which may explain his next job: bartending at the American Airlines Admirals Club at JFK and LaGuardia airports. One day in 1970, at LaGuardia, he was re-acquainted with Clarry Pell, who convinced him to come back into the fold via a weekend gig at Greentree. Good-willed and a natural storyteller, Jack tried to explain court tennis and the Greentree estate to his fellow workers at the airports, but he told me with a laugh that he gave up. None of it made any sense to anyone living in the real world, he said. Jack was the appointed gatekeeper for our weekend morning games. Pete and Jimmy Bostwick had carte blanche; Pete would organize the games with Jack Hickey. In addition, and variously over the years, Long Islanders such as Robert Pilkington, Dinny Phipps, Jimmy Knott, Rusell Corey, and Robin Geddes rotated in and out of play. Sometimes players would come out from New York. The building was ours, other than one fellow who came early in the morning to turn up the heat, and then waited to greet us at the locker room door to make sure all our needs were met.

Though I wish I had, I made no notes of my weekend visits to Greentree. As I’ve grown older, I’ve wondered what was real and what was imagined, embellished, over the 25 years since my last game there. A place already magical in my mind, forgive me if I go astray. I recall that the court tennis building contained eight guest bedrooms, appointed with claw-footed bathtubs and pedestal sinks with two taps, all in a line behind the main wall. The living room set back from the dedans contained walls of leather-bound books overhung with library lights; impressionist paintings by Monet, Picasso, Sisley, and Renoir (much of the Whitney’s art treasures had been shipped off to adorn the eponymous Whitney Museum of Art in NY), and various sitting rooms. At the base of the floor-length curtains, sat little gray boxes with Geiger-counter like needles, likely measuring humidity to protect the art. Downstairs: a large, tiled pool with marble decking and stand-up individual steam lockers, a squash-tennis court, a dozen changing booths, showers, and baths — with piles of Greentree towels set out on white painted tables. The stairway walls were covered with framed sporting prints — horses and dogs, mostly — each with a brass plate to describe pedigree and origin. Many were portraits of the thoroughbreds that Jock Whitney entered in the Kentucky Derby or used for polo matches.

Back to the man who greeted us… I can’t recall his name. There were no estate-issued uniforms. Jack Hickey and everyone else I saw wore plain shirts, sweaters or puffy vests, normal winter stuff. But they had been schooled: they referred to “Mrs. Whitney” and how things were done at Greentree. All of us were complicit in something, we played our roles. Somehow we knew none of this could last, the sweep and grandeur of the estate lifted from 19th century England, a green oasis amidst the snarl of Long Island suburbs. I used to imagine these Sunday workers going home to their families in Valley Stream or Queens or Jamaica to explain the impossibility of Greentree.

During our weekend games, we never saw Mrs. Whitney. She was aging. Still, there was always someone of some mysterious rank or position, an emissary, who would make the long walk down the glass corridor — lined with flowering pots, ferns, and orchids, even in winter — that connected the main house to the court tennis building. The emissary brought word from Mrs. Whitney herself, conveying her regrets in not being able to greet us personally, and her sincerest wishes that we enjoy the tennis. The funny thing is, we always took him seriously and reciprocated with our own well-wishes. For all we knew, the man had never met Mrs. Whitney. But that was the cynicism of the outside world slipping in, the reaction of my work-a-day self. No, here, your word mattered. Somehow your best self, if not your best tennis, came out.

For decades, the building came alive one weekend in December, as Whitney Cup teams arrived, jammed the locker room, snooped around the building and contested for bragging rights. To make a Whitney Cup team was to earn a two-day pass to another world.

My grandfather John Bell, and my father George Bell, both played for many Philadelphia teams, joined by Jimbo and Bill Van Alen, John Mirkll, Bill Linglebach, Edward (Ned) Edwards, stalwart Bill Vogt, and others. When you weren’t on the court, you were in a coat and tie. I was lucky enough to contest a number of Whitney Cup weekends at Greentree in the 1980s, playing for Philadelphia, New York, or New-Bos-Tux. In those days New York had enough dominance that it leveled the playing field by splitting up the best players. As autumn deepened, and the Whitney Cup approached, Ralph Howe, Kevin McCollum, Henry Bunis, Peter De Svastich, Randy Jones, Willie Surtees, Simon Aldrich, Gene Scott and I talked endlessly about team combinations and who would play in what order, for what city — an engaging, if wasteful, Whitney tradition. By that time, no one was invited to stay in the Greentree bedrooms anymore. Sunday lunch for players, wives, and families was the culmination of the weekend. Though the social aspects of the Whitney had shrunk, we were still free to prowl around the building. During our explorations, I recall the look on my fellow conspirators’ faces — partly the awe of spying beautiful things — Remington sculptures and polished brass clocks — but mostly the smirk of recognition that we were way over our heads.

One Sunday lunch I got up the courage to say hello to Mrs. Whitney, who still attended the event in those days, and was regally positioned in the library behind the dedans. I vaguely recall asking Peter DiBonaventura if it was OK to approach her. I said my name, and then nervously rushed to give her the names of my grandfather and father as Whitney Cup players of the past. As she held my hand, she stared at me. Then she said, slowly, Of course, I remember Jack Bell.

We continued to compete at Greentree through the ‘90s, though as Mrs. Whitney’s health declined, the curtain came down on our Sunday games. The Cup moved back to the R&T in 2001, as if a new century was just too much for the estate to bear. Worse, it meant that make-believe time was over: the sense that I was destined for a life of leisure — a feeling made inchoate in me by visits to Greentree – vanished.

I exalted Greentree, in part, because it was associated with such a touching time in my life. My wife Carrie and I moved from NYC to nearby Glen Cove as newlyweds, bought our first house there, and had our first two sons there. In fact, shortly after my father’s death from cancer, George III, our firstborn, arrived at North Shore Hospital in Manhasset, which was very close to Greentree. Carrie went into labor during the final weekend of Wimbledon. Her pediatrician, Glen Kaufman, a tennis fanatic, kindly invited me into the doctors’ lounge to watch the semi-finals while Carrie rested before her contractions sped up — not my best move. At some point, for the benefit of those in scrubs, I started babbling about how happy I was that our child would be born close to Greentree, just down the road, and that court tennis was the progenitor of tennis as we know it, there was a roof in the court and the racquets were lopsided. Our pediatrician was an educated doctor with a Porsche. Regretting his invitation, he stared at me for a moment then went back to watching Wimbledon. In a few hours, he would preside over Georgie’s birth, then our Henry two years later. Soon after that, I accepted a job with Excite, an early search engine in Silicon Valley, at a time when almost no one yet had an email address . We went west. For one reason or another, I didn’t set foot on a court tennis court for another ten years.

Generally, we didn’t shower at the estate after our Sunday games, we didn’t want to make a fuss. As I collected my bats and headed for the door on my last weekend at Greentree, I saw an estate worker I hadn’t met before, carrying a wooden toolbox with brass hinges. He had just come into the building and was stomping his feet on the ground and blowing into his hands. Good game, he asked. We exchanged names, and I shook his hand. There was a confidence about him that I liked. I asked him what he did. Odds and ends, he said, but mostly I take care of the clocks on the estate. With a smile, he added, the guys call me the clock winder.

Note: Thanks to Jim Zug for filling in my memories, and not tearing down my fictions.